Private credit managers raise capital, typically from large institutional investors with long-term investment horizons (pension funds, insurance companies, sovereign wealth funds, and the like), which is managed in a closed-end fund, usually with a long lock-up period. That is used to lend directly to corporates with the typical borrower being of a kind deemed either too large or too risky for bank lending but too small to raise funds on the public markets.

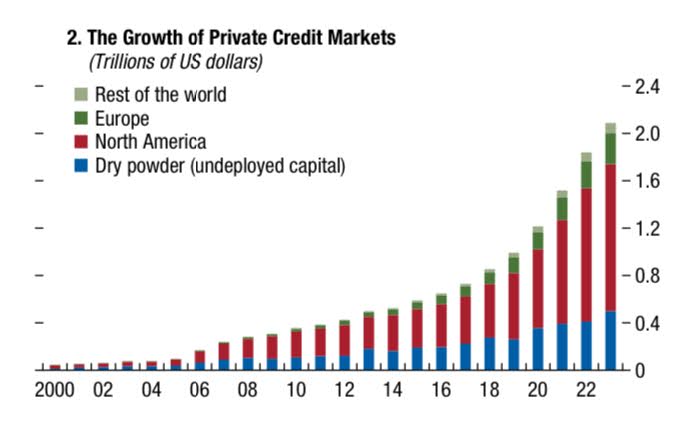

The IMF’s numbers suggest that whilst private credit truly was a niche pursuit around the turn of the millennium it has taken off in the years since the 2007-2009 financial crisis and especially over the past five years, especially in North America.

Whether the market size has actually moved from around $0.3tn to $2.1tn or $3tn in the space of around 16 years since 2008, no one doubts that it has grown a great deal.

The reasons for this growth are not too hard to fathom.

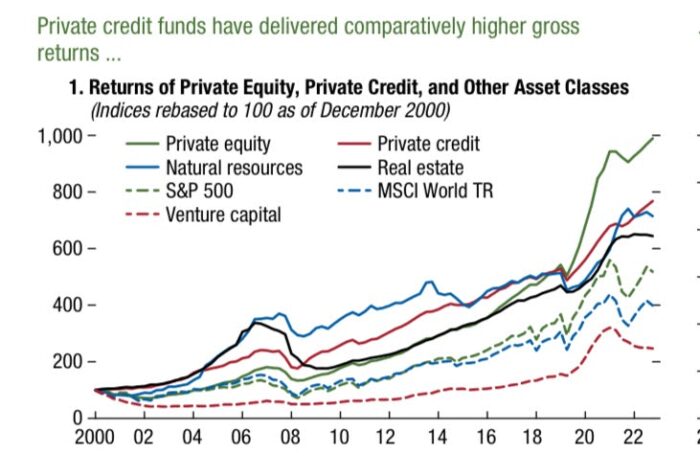

The low interest rate environment that prevailed in the decade following the financial crisis saw investors seeking out new ways to buy their assets to work. The same sort of factors that drove the growth of inflows into private equity were at play. The returns available, as noted by the IMF, have been very strong – even when compared to the comparative (by no means weak) returns on public markets over the same time period.

Those returns help explain the growth in the size of private credit assets under management but the demand for private credit borrowing from firms probably owes more to financial regulation.

In the aftermath of the global banking crisis regulators increased capital requirements on banks and, in general, encouraged them to hold safer assets by making greater use of risk weightings. Taken together, this has lowered the ability of banks to extend credit to the kind of mid-market firm that typically borrows from private credit funds.

There is little doubt that the typical borrower from such a fund tends to be at the higher end of the risk scale. If this were not the case, then the returns made by such funds over the last decade or so would be very hard to explain away.

The IMF’s analysis earlier this year was especially helpful.

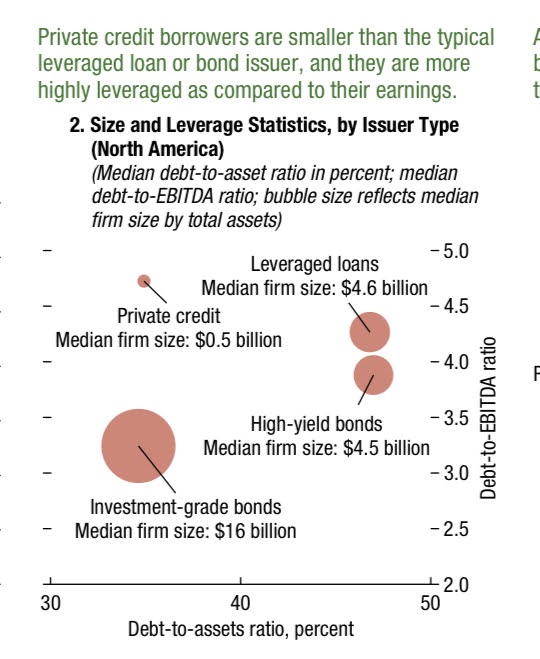

Comparing the median borrowers in the North American private credit market, leveraged loan market, high yield bond markets, and investment-grade bond markets is a useful exercise.

Whilst the debt-to-assets ratio for private credit borrowers tends to be low, the debt-to-EBITDA (or earnings before interest, tax, depreciation, and amortization) ratio is notably higher. In other words, the available cash to meet interest payments tends to be on the lower side.

The growth of private credit has no doubt helped to fill an important gap in credit markets – providing debt finance to firms that might have otherwise struggled to raise it in the post-2008 tighter regulatory environment. The IMF reckons it has had a positive impact on global growth and capital investment. It has also been a very useful source of returns for those institutions exposed to it.

But has it also brought with it new risks?

A useful IMF blog post earlier this year helped to summarize the potential issues. For a start, the underlying borrowers – as noted – tend to be higher risk. More generally though the Fund notes that as private credit assets rarely trade, market data cannot be used to price them and they are instead marked-to-model rather than market. That makes the underlying health of the private credit funds more opaque. The levels of leverage employed are also somewhat cloudy, as are the interconnections between the less regulated private credit complex and the regulated – and systemically vital – banking sector.

In the view of the Fund whilst the industry itself and its rapid growth does not necessarily create a new systemic risk that policymakers have to focus on, it should – at the very least – warrant closer monitoring and, ideally, be subject to the better disclosure standards so that regulators can get a clearer picture of what is going on.

Some argue that the transfer of the riskiest lending away from banks and towards newer entities may actually reduce risk in the financial system as a whole. With long lock-up periods for private credit funds, the maturity mismatch between deposits and loans that can cause banks trouble is less apparent.

This week the Clark Center’s Finance Expect Panel weighed in. 61% of respondents, weighted by confidence, agreed that the growth of the sector is substantially higher because of regulations that disincentivize banks from lending to below-investment grade counterparties.

On the more interesting question, opinion was divided. Asked whether the large increase in private – rather than – bank credit had materially reduced systemic risk in the finance system, a plurality of respondents – weighted by confidence – were uncertain.

Over the last decade and a half the riskiest corporate lending has moved away from the balance sheets of the regulated banks and into a more opaque sector. Without more information and disclosure, it is too early to say what the long term consequences will be.